- within Privacy, Consumer Protection and Environment topic(s)

Introduction

There is no doubt that the recent implementation of the new tariffs in the first half of the year on global imports to and exports from the United States has significantly reshaped the global trade landscape. While much attention has been given to the broader economic and political implications of such measures, their impact on multinational groups (MNEs) and their daily operations, including the areas of transfer pricing (TP) and customs, has been profound. In an environment of increasing tax compliance and administrative burden by the MNEs, these tariffs, beyond increasing the direct cost of imports, have wide implications on TP and customs valuation, challenging long-standing intercompany pricing policies and potentially raising questions around consistency.

In this response, the authors aim to explore how the tariffs influence supply chain strategies and TP models in Luxembourg.

1. In your jurisdiction, how do the tax and customs departments interact? Are they operating separately or collaborating, especially considering their potentially conflicting interests (e.g., higher import prices leading to higher import duties but lower local profits)?

Luxembourg is well known for its tax environment, efficient administration, strategic location within the EU, and multilingual personnel. The country's tax, value added tax ("VAT"), and customs matters are administered by three main bodies:

- The Direct Tax Administration (Administration des Contributions Directes or "ACD"), being responsible for the assessment and collection of all direct taxes, e.g., corporate income tax, municipal business tax, net wealth tax, withholding tax, and personal income tax. The ACD performs TP and other tax audits and is the competent authority for mutual assistance procedures and advance pricing agreements.

- Registration Duties, Estates, and VAT Authority (Administration de l'Enregistrement, des Domaines et de la TVA or "AED"), handling, among others, VAT, registration, and stamp duties.

- The Customs and Excise Administration (Administration des Douanes et Accises or "ADA"), overseeing customs duties and controls, excise duties (e.g., on alcohol, tobacco, etc.), and import and export compliance.

While these authorities operate independently, they often coordinate and exchange information. The exchange of information between the ACD and the AED, on the one hand, and between the AED and the ADA, on the other hand, are expressly provided for in Luxembourg law. However, Luxembourg law remains silent on the exchange of information between the ACD and the ADA.

The exchange of information is, in principle, possible for limited reasons, namely:

- Between the ACD and the AED, such an exchange of information mainly concerns the correct assessment and collection of taxes, duties, fees, contributions, and VAT that fall within their respective areas of competence using automated or non-automated processes. The information exchanged may consist of any information, document, report, or deed discovered or obtained by the requested authority and may then be invoked by the requesting authority. Automated processes must be carried out by means of data interconnection and with the guarantee of secure, limited, and controlled access.

- Between the AED and the ADA, such an exchange of information mainly concerns the correct assessment and collection of import and export duties, excise duties, road vehicle tax, and VAT, using automated or non-automated processes. Automated processes must be carried out by means of interconnection or consultation of data through direct access to personal data files, provided that such access is secure, limited, and controlled.

2. Please explain the interaction between transfer pricing methods (e.g., as outlined in the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines) and customs valuation methods (e.g., as described in the WTO Valuation Agreement) in your jurisdiction.

Depending on the type of transaction, the countries involved, and the goods traded, cross-border transactions between related parties are scrutinized not only by the AED in the course of TP audits but also by the ADA for import valuation. While the set of rules governing TP and import valuation aims to ensure that prices reflect market conditions, they differ fundamentally in purpose, methodology, and timing. Such differences may have impacts on MNEs, which often use a single intercompany price for both customs and tax purposes. Yet, the two regimes assess pricing under different grounds and objectives, further leading to challenges or adjustments in audits if the price does not meet the expectations of both sets of rules.

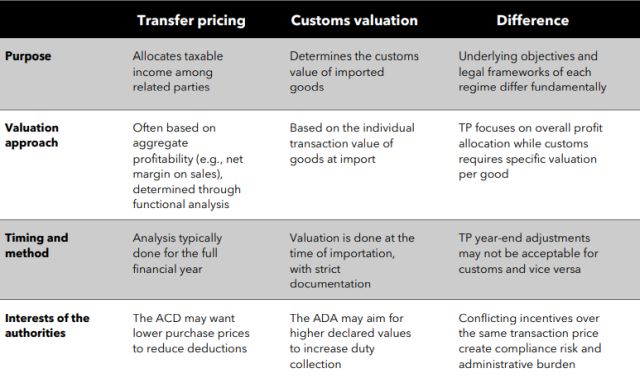

While TP aims to allocate taxable income across related parties, the customs valuation determines the customs value of imported goods, the primary basis of which is the "transaction value." The key differences between TP and customs valuation can, on a high-level basis, be summarized in the table below:

To date, in Luxembourg there is no administrative guidance on the interaction between TP methods and customs valuation methods. Thus, taxpayers should make sure to comply with Luxembourg law, the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations, and the WTO Valuation Agreement, as the case might be.

In practice, the authors see that key Luxembourg taxpayers in the air transport sector attribute great importance in identifying the commodities that fly onboard their aircrafts to make sure they are shipped with all documentary requirements in accordance with legal and commercial frameworks by implementing export control systems to ensure that they comply with applicable export control regulations at all times.

3. From a supply chain perspective, MNEs may consider implementing restructuring strategies to mitigate the impact of higher customs duties. Transfer pricing strategies employed by MNES may include lowering operating margin levels for limited risk distributors, or converting contract manufacturers into toll manufacturers, for example.

How would general anti-abuse provisions in your jurisdiction address such strategies, assuming the behavior of parties aligns with economic reality and the new or modified contractual agreements?

The general anti-abuse rule ("GAAR") for direct taxes is codified in §6 of the tax adaptation law and provides that an abuse of law is constituted when: "The legal route which, having been used for the main purpose or one of the main purposes of circumventing or reducing tax liability that defeats the object or purpose of the tax law, is not genuine having regard to all relevant facts and circumstances."

Additionally, paragraph 6 of the StAnpG provides that "the legal route, which may comprise more than one step or part, shall be regarded as non-genuine to the extent that it was not used for valid commercial reasons reflecting economic reality."

The GAAR therefore targets transactions that have been put in place for the main purpose, or one of the main purposes, of obtaining a tax advantage that defeats the object or purpose of the applicable tax law, or are not genuine (e.g., are not put in place for valid commercial reasons that reflect economic reality), considering all the relevant facts and circumstances.

With regards to the burden of proof it is, in principle, for the ACD to demonstrate that the constitutive elements of abuse of law are met. However, this allocation of the burden of proof cannot entail that the ACD would have to prove the impossibility of an economic justification of the structure used. Instead, the ACD must make the absence of an economic justification plausible. The burden of proof then shifts from the ACD to the taxpayer as soon as the ACD has shown, on the basis of a body of evidence, that the conditions of abuse are likely met. The taxpayer must then establish the economic rationale for the chosen path. These economic reasons must be real and must entail a sufficient economic advantage that goes beyond the tax advantage obtained.

One thing is for certain: the tariffs are here and are here to stay - at least for the foreseeable future, thus affecting taxpayers and increasing the direct cost of imports. To that end, taxpayers may seek alternatives and restructuring opportunities to adjust to the new economic reality. Should that be the case, it is recommended that the affected taxpayers properly document the business and economic rationale behind their decision to restructure so that the risk of abuse would be mitigated.

4. How are customs authorities in your jurisdiction responding to transfer pricing year-end adjustments? What are the specific requirements and procedures for decreasing customs duties following a year-end adjustment?

A key tension arises in the relationship of TP and customs when a price acceptable under TP rules is not acceptable for customs, and vice versa. For example, year-end TP adjustments intended to align profits with the arm's length principle may conflict with customs rules, which typically require declared values to be final at the time of importation. Nevertheless, the ACD, the ADA, and Luxembourg case law remain silent without having issued any administrative guidance, circular, or judgment on the topic, thus creating legal and tax uncertainty.

It remains to be seen how the ACD and the ADA will cooperate with each other on tackling these pragmatic obstacles in the context of this new economic reality.

Originally published by Bloomberg Tax.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.