- with readers working within the Insurance industries

Artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly changing the way people create and invent. The applicable intellectual property laws and procedures are working to keep up with this advancing technology. Intellectual property laws and rules focus on human creativity. Generative AI produces results that are not directly programmed, but trained. Hence, AI outputs are not fully predictable. This discussion takes a look at the current laws, rules and guidelines of US patents and copyrights, to see how AI-assisted creations fit into these parameters.

US Patent Law: AI Is Not an Inventor

On the patent side, the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals articulated that AI by itself cannot be listed as an inventor.1 The applicant listed the AI program as the sole inventor on the patent application. The court decided that an inventor must be a natural person, since the inventorship statute of the Patent Act lists an inventor as an "individual".2 The court did not address AI-assisted inventorship, since no individuals were listed as inventors.

US Patent Procedure: AI-Assisted Inventorship

With the prevalence of AI-assisted development, it is likely (and common) that AI-assistance is utilized when developing inventions. In 2024, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) provided Inventorship Guidance for AI-Assisted Inventions.3 These guidelines set forth that AI-assisted inventions are not categorically unpatentable as long as a natural person provides a significant contribution to the invention.4 The Patent Office guidelines state that "applications and patents must not list any entity that is not a natural person as an inventor or joint inventor, even if an AI system may have been instrumental in the creation of the claimed invention."5 The guidelines apply to utility, plant, and design patents & applications.6

When determining inventorship, the guidelines refer to inventorship factors (known as the Pannu factors) developed in the context of joint inventorship in a case that did not involve AI.7 In the Pannu case, the court found that each named inventor must contribute in some significant manner to the conception or reduction to practice (discovery or prototype) of the invention and the guidelines apply this caselaw to AI-assisted inventions.8

The guidelines provide five enumerated guiding principles that are derived from the Pannu factors, to assist applicants in determining proper inventorship in AI-assisted inventions.9 First, "[a] natural person's use of an AI system in creating an AI-assisted invention does not negate the person's contributions as an inventor."10 Second, "[m]erely recognizing a problem or having a general goal or research plan to pursue does not rise to the level of conception."11 The mere presentation of a problem to AI is contrasted in this guiding principle with an inventor's significant contribution in how the AI prompts are instructed.12

The third guiding principle states "[r]educing an invention to practice alone is not a significant contribution that rises to the level of inventorship."13 In other words, recognizing the significance of AI output is not inventorship, while adding a significant contribution to the output is inventorship.14

The fourth guiding principle provides:

A natural person who develops an essential building block from which the claimed invention is derived may be considered to have provided a significant contribution to the conception of the claimed invention even though the person was not present for or a participant in each activity that led to the conception of the claimed invention.15

This guiding principle further expounds that the inventive significant contribution may lie within the design, build, or training of the AI system.16

The fifth guiding principle posits: "[m]aintaining 'intellectual domination' over an AI system does not, on its own, make a person an inventor of any inventions created through the use of the AI system."17 Thus, ownership or control of the AI system is not an inventive significant contribution.

Copyright Law: Author Must Be Human

In the context of copyrights, US courts have consistently held that authors must be people. In the 'monkey selfie' case, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals decided that an animal is not an author within the meaning of the Copyright Act.18 Artwork made with AI and without any human contribution was denied copyright registration by the Copyright Office.19 The applicant is currently seeking review of the denial at the US Supreme Court.20

Copyright Procedures: AI-Assisted Authorship

The Copyright Office issued guidance for Works Containing Material Generated by Artificial Intelligence in 2023, and then a report in 2025 on copyrightability with AI.21 Both acknowledged existing US Supreme Court precedence that "sweat of the brow" alone is insufficient for copyright protection.22 "To be sure, the requisite level of creativity ... possess[es] some creative spark, 'no matter how crude, humble or obvious' it might be."23 After analyzing the case law:

The Office concludes that, given current generally available technology, prompts alone do not provide sufficient human control to make users of an AI system the authors of the output. Prompts essentially function as instructions that convey unprotectible ideas. While highly detailed prompts could contain the user's desired expressive elements, at present they do not control how the AI system processes them in generating the output.24

The Copyrightability Report reasons: "[t]he fact that identical prompts can generate multiple different outputs further indicates a lack of human control."25 "Repeatedly revising prompts does not change this analysis or provide a sufficient basis for claiming copyright in the output."26 The Copyrightability Report seems optimistic, noting "[t]here may come a time when prompts can sufficiently control expressive elements in AI-generated outputs to reflect human authorship."27

AI-Assisted Example 1: Inventor, But Not an Author?

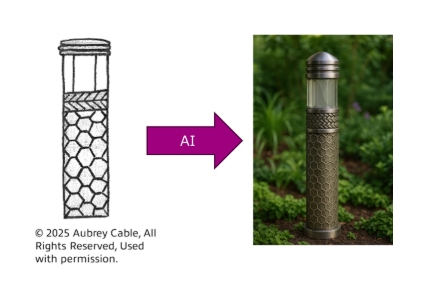

In order to compare and contrast the patent and copyright procedures, let's consider a potential artistic design, such as a garden bollard. First, imagine someone (such as co-author Aubrey Cable) asks an AI program (ChatGpt) to draw a garden bollard by inputting the prompt illustrated below. The AI output is also provided below.

No new functionality is provided in the proposed design, and therefore utility patent protection is not considered. For this example, inventorship is viewed with an eye toward US design patentability. A design patent is directed to an ornamental design as shown and described in the design patent application.28 Since the overall aesthetic design would claim many features that were contributed by human Aubrey Cable, she has made a significant contribution to the invention to be claimed. Under the patent guidance, Aubrey's significant contribution should meet the requirements for inventorship.

Applying the copyrightability guidelines, "prompts alone do not provide sufficient human control", and "identical prompts can generate different outputs".29 It is unlikely that Aubrey will be considered an author since she entered prompts alone, which can result in different outputs.

In this scenario, Aubrey has made a significant contribution to be an inventor and file a design patent application, but may not have enough control to be an author to register a copyright.

AI-Assisted Example 2: Inventor and Author

Please consider again the garden bollard example. However, in this second hypothetical, Aubrey hand-sketched the design as depicted below, which was input into AI with a request to "recreate this drawing of a garden bollard and retain each key feature and detail of the drawing."

Similar to the analysis in the first example, a design patent claim would include one or more features that were conceived by Aubrey. Therefore, she is an inventor under the design guidelines and can pursue design patent protection.

In this second example, Aubrey generated an artistic sketch before inputting the sketch into AI. And once she uploaded her sketch to AI, she requested that it maintain the key features. Under this example, Aubrey maintained human control over the design, from input to output. In other words, she utilized AI for predictable and controlled refinement of the design, not generation of the design. Therefore, Aubrey is likely an author sufficient to apply for copyright registration.

Summary

It is early in the development and application of caselaw and procedures for AI-assisted intellectual property, and the intellectual property practices will likely further develop as new issues are faced by the courts, the USPTO, and the Copyright Office.

It is worth noting that if human input into AI includes a significant contribution to patent claims and the output from AI includes that significant contribution, then the human is an inventor. Or, if the human adds a significant contribution to an AI output, and that significant contribution is claimed, then the human is an inventor.

Similarly, if a human inputs an artistic expression into AI, and controls the AI output to include that expression, then the human is likely an author that can apply for copyright registration. If the human adds an artistic expression to AI output, then the human is also likely an author.

Footnotes

1. Thaler v. Vidal, 43 F.4th 1207 (Fed. Cir. 2022), cert. denied, 143 S.Ct. 1783 (2023).

2. Id., 35 U.S.C. § 100(f) & (g) (2015).

3. 2024-02623 (89 FR 10043).

4. Id., at Summary and Subsection III.

5. Id., at Subsection III.

6. Id., at Subsection V(A).

7. Pannu v. Iolab Corp., 155 F.3d 1344 (Fed. Cir. 1998).

8. Id., at 1351; and Inventorship Guidance for AI-Assisted Inventions, 2024-02623 (89 FR 10043) at Subsection IV(A).

9. Inventorship Guidance, at Subsection IV(B).

10. Id., at Subsection IV(B)(1).

11. Id., at Subsection IV(B)(2).

12. Id., at Subsection IV(B)(2).

13. Id., at Subsection IV(B)(3).

14. Id., at Subsection IV(B)(3).

15. Id., at Subsection IV(B)(4).

16. Id., at Subsection IV(B)(4).

17. Id., at Subsection IV(B)(5).

18. Naruto v. Slater, 888 F.3d 418 (2018).

19. Thaler v. Perlmutter, 130 F.4th 1039 (D.C. Cir. 2025), rehearing denied, rehearing en banc denied, pet. cert. pending, No. 25-____ (Oct. 9, 2025).

20. Id.

21. 88 Fed. Reg. 16190 (Mar. 16, 2023), Copyright and Artificial Intelligence, Part 2: Copyrightability (Jan 2025).

22. Copyrightability Report at 8, Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Co., 499 U.S. 340, 352-61 (1991).

23. Copyrightability Report at 8-9, Feist Publications, 499 U.S. at 345.

24. Copyrightability Report at 18.

25. Id., at 20.

26. Id., at 20.

27. Id., at 21.

28. 37 C.F.R. § 1.153(a), (2012).

29. Copyrightability Report at 18 and 20.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.