- within Intellectual Property topic(s)

- in Canada

- with readers working within the Media & Information, Retail & Leisure and Law Firm industries

- within Intellectual Property, Wealth Management and Antitrust/Competition Law topic(s)

The apparel and fashion industry is rife with intellectual property issues and disputes. Particularly in the past twenty years, courts have grappled with the competing interests and arguments of apparel designers, online re-sellers, and others seeking to use apparel companies' trademarks and designs in their products or creative endeavors. This article summarizes some of the most notable U.S. intellectual property cases in the industry.

Christian Louboutin S.A. v. Yves Saint

Laurent America, Inc.

(2012)

Color Trademarks and Trade Dress

Since 1992, Christian Louboutin (Louboutin), the designer and retailer of high-fashion women's footwear and accessories has covered the sole of its women's footwear with a high-gloss red lacquer. After years of hefty investment into building a reputation and goodwill for the red sole, Louboutin successfully registered the red sole as a trademark (trade dress) with the United States Patent & Trademark Office (USPTO) in 2008.

Credit: Arroser (Wikipedia)

In 2011, Yves Saint Laurent (YSL), the French luxury fashion house, launched a campaign for its monochrome shoes. The monochrome shoes included purple, yellow, green, and red shoes. The red shoe was all red, including a red insole, heel, upper, and outsole. Louboutin filed suit against YSL alleging trademark infringement under the Lanham Act for YSL's use of the red sole.

On the issue of protectability, YSL initially prevailed as the District Court denied Louboutin's motion for preliminary injunction, holding that the use of a single color was only protectable as a mark if it "acts as a symbol that distinguishes a firm's goods and identifies their source, without serving any other significant function." Christian Louboutin S.A. v. Yves Saint Laurent America Holding, Inc., 696 F.3d 206, 214 (2d Cir. 2012) (emphasis in original) (quoting District Court decision). The District Court found that the use of the color red by Louboutin for footwear was functional, and not distinctive, and therefore did not qualify as a trademark.

However, on appeal, the Second Circuit overturned the District Court's holding on this issue, noting that the Supreme Court in Qualitex Co. v. Jacobsen Products Co., 514 US 159 (1995) had "specifically forbade the implementation of a per se rule that would deny protection for the use of a single color as a trademark in a particular industrial context." Christian Louboutin S.A. v. Yves Saint Laurent America Holding, Inc., 696 F.3d 206, 223 (2d Cir. 2012).. Because the red sole mark had acquired secondary meaning among consumers as a distinctive symbol identifying the Louboutin brand, the Second Circuit deemed it could be protected as a trademark. Nonetheless, the Second Circuit upheld the District Court's denial of the preliminary injunction because it found that YSL's use of a red sole for its red monochrome shoe was not use of the mark nor confusingly similar to Louboutin's mark. Louboutin continues to enforce its red sole mark around the world.

Tiffany & Co. v. Ebay,

Inc. (2010)

Liability of Online Marketplaces

In one of the key cases challenging online retailers for selling counterfeit items, the renowned fine jewelry maker Tiffany & Co. (Tiffany) sued eBay for allowing counterfeit Tiffany products to be sold on eBay.com. Tiffany's claim centered on the fact that eBay's platform was being used by third parties to sell a large number of counterfeit goods, even though that knowledge was general and not with reference to particular items.

The issue centered on whether eBay could be held liable for trademark violations committed by third-party vendors when eBay itself was not the seller. The Second Circuit held that eBay was not liable for contributory trademark infringement. Tiffany (NJ) Inc. v. eBay, Inc., 600 F.3d 93 (2nd Cir. 2010). The Court reasoned that the platform was not liable so long as it took down listings of counterfeit goods upon notification by trademark holders, and Tiffany had not established that eBay "knew or should have known" of the counterfeit products. Id. at 107. The Court emphasized that the burden of policing trademark rests with the trademark owner, not the online marketplace.

Nonetheless, a significant factor in the Court's analysis was the fact that eBay was investing substantial resources into combatting counterfeit activities on its platform. The Court was also persuaded by the fact that plenty of authentic Tiffany goods were sold on eBay, so requiring it to ban all Tiffany merchandise listings would significantly impair the legal secondary market.

The Tiffany decision has been cited widely in cases that deal with the question of whether an e-commerce marketplace can be contributorily liable for trademark violations. So long as online marketplace providers make reasonable efforts to combat counterfeiting and take action to remove counterfeit goods from their sites, they will likely not be held liable for contributory infringement. Most large online retailers now have programs in place to allow trademark owners to lodge complaints about counterfeit goods.

Since Tiffany, the Shop Safe Act, which has faced several revisions since its initial introduction in 2020, was re-introduced in Congress in September 2023 but did not pass. The Act would seek to hold e-commerce entities accountable for their vendors who sell counterfeit or otherwise infringing products.

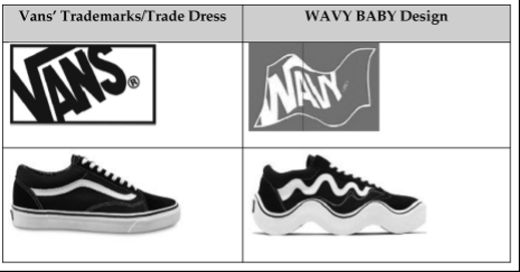

Vans, Inc. v. MSCHF Product Studio,

Inc. (2023)

Trade Dress Infringement, Artistic Expression, Parody

and the First Amendment

The well-known footwear brand Vans sued MSCHF Product Studio (MSCHF), a Brooklyn-based art collective, over its "Wavy Baby" sneakers which bore a resemblance to Vans' iconic "Old Skool" shoes, albeit with a wavy sole design. Vans alleged that the Wavy Baby sneakers infringed on their trademark and trade dress, leading to consumer confusion and harming their brands. Vans sought an injunction to stop the sale of the Wavy Baby sneakers.

MSCHF, whose works had been displayed in museums, galleries, and art shows worldwide, asserted that the Wavy Baby sneakers were a form of artistic expression and parody, designed to "start a conversation about consumer culture . . . by participating in consumer culture," and were protected under the First Amendment. MSCHF further argued that the wavy design was a creative reinterpretation and parody of Vans' classic shoe and that no reasonable consumer would confuse the Wavy Baby with Vans' Old Skool shoe due to differences in the brands' respective marketing. MSCHF also claimed that their shoe transformed the "once iconic shoe into the modern, wobbly, and unbalanced realities." Vans, Inc. v. MSCHF Prod. Studio, Inc., 88 F.4th 125, 130 (2d Cir. 2023).

The District court granted Vans' motion for preliminary injunction and the Second Circuit Court affirmed reasoning that the Wavy Baby sneakers' overall appearance was likely to cause consumer confusion despite their deviations from the "iconic" Vans shoes. More importantly, based on the Supreme Court's decision in Jack Daniel's Properties, Inc. v. VIP Products LLC, 599 U.S. 140 (2023), the Second Circuit rejected MCSCH's argument that its actions were protected under the First Amendment, reasoning that MSCH had used Vans' marks and trade dress, at least in part, as trademarks (source identifiers). Therefore, the heightened showing of confusion required by Rogers v. Grimaldi, 875 F.2d 994 (2d Cir. 1989) in cases involving parody did not apply.

Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands,

Inc. (2017)

Some Copyright Protection for Fashion Designs

In general, copyright law does not typically protect apparel designs as apparel is considered a "useful" article under the Copyright Act. However, the Supreme Court's decision inStar Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc., 580 U.S. 405 (2017) explained when certain elements of an apparel's design could be protected by copyright.

Plaintiff/Respondent Varsity Brands (Varsity), a prominent company in the cheerleading uniform industry, had obtained copyright registrations for over 200 two-dimensional designs appearing on the surface of its uniforms and other garments. Some of the designs consisted of stripes, chevrons, and zigzags. Varsity sued Defendant/Petitioner, Star Athletica (Star), for copyright infringement, alleging that Star's cheerleading uniform designs in a catalog infringed on five of Varsity's copyrighted designs.

Five designs at issue, by Varsity Brands

On a summary judgment motion, Star argued that plaintiff Varsity's designs were not entitled to copyright protection because the designs were "utilitarian," identifying the garments as cheerleading uniforms, and therefore not "physically or conceptually" separate from the uniforms. The District Court agreed and dismissed the claims. On appeal, however, the Sixth Circuit reversed and found that Varsity's design were protectable as they were "separately identifiable" from the uniforms.

Although the Copyright Act does allow for protection of artistic elements in "useful articles," it does so provided that the "pictorial, graphic, or sculptural features ... can be identified separately from, and are capable of existing independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article." 17 U.S.C. § 101. But the metes and bounds of this "separation" had been the subject of many varying court decisions.

Varsity had argued that their designs were artistic elements that deserved copyright protection because they existed independently of their uniforms' functional aspects. That is, the designs were purely artistic and had no effect on the uniform's utility. Star countered that the designs were intrinsically linked to the uniforms' functionality because they were essential to their aesthetic appeal and marketability of the uniforms. By integrating these designs, the uniforms would properly serve their function of creating a striking and cohesive team appearance. Star thus argued that granting copyright protection of the designs to Varsity would improperly extend copyright protection to the functional aspects of the uniforms.

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Varsity, finding that if the designs can be perceived as two or three-dimensional works of art separate from the useful article (the uniforms) and would qualify as protectable pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work on their own, then they are eligible for copyright protection.

Star Athletica was seen as a victory for apparel designers as many prior cases had found that apparel designs were not copyrightable. Still, the "separability" test articulated in the case, namely, that aesthetic elements of clothing can be protected by copyright law if the elements can stand on their own as works of art, has been criticized by some commentators as providing little guidance on how the law will be applied in other cases.

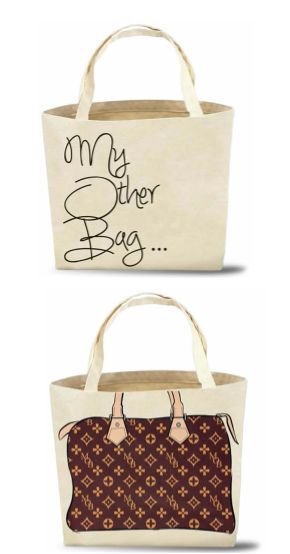

Louis Vuitton Mallatier S.A. v. My

Other Bag, Inc.

(2016)

Parody and Trademark Law

In another case involving the First Amendment defense of parody, My Other Bags, Inc. (MOB) was able to successfully defend itself against claims of trademark infringement, trademark dilution, and copyright infringement brought by luxury fashion house Louis Vuitton. Louis Vuitton Mallatier, S.A. v. My Other Bag, Inc., 156 F. Supp. 3d 425, 435 (S.D.N.Y. 2016). Louis Vuitton sued MOB for selling canvas tote bags that had "My Other Bag" printed on one side and images of renowned handbags from high-end brands like Louis Vuitton on the other side. See below. Louis Vuitton took offense to MOB's tote bag designs and argued that its products caused consumer confusion and harm to the Louis Vuitton image.

Louis Vuitton argued that the parody defense was not applicable because the bags were not "transformative" enough and merely copied the Louis Vuitton design without significant commentary or critique. MOB moved for summary judgment, arguing that their bags were clearly parody, and therefore protected under the First Amendment.

The District Court held in favor of MOB, concluding that the tote bags constituted valid parody of Louis Vuitton products. The difference in quality, price, and presentation between MOB's totes, which were frequently used for groceries and gym clothes, and Louis Vuitton's luxury bags were evident enough to avoid confusion according to the Court. The Court also noted that the bags were a "play on the well-known 'my other car....'" bumper sticker, and that "almost cartoonish renderings" of the Louis Vuitton bag on the MOB bags "build significant distance between MOB's inexpensive workhorse totes and the expensive handbags they are meant to evoke." 156 F. Supp. 3d at 435. As the Court held, a parody "clearly indicates to the ordinary observer 'that the defendant is not connected in any way with the owner of the target trademark.'" Id.

Six years later in another parody case, Vans, Inc. v. MSCHF Prod. Studio, Inc. (the Wavy Baby shoe case discussed above),the District Court distinguished Louis Vuitton Mallatier, S.A. v. My Other Bag, Inc. on the grounds that the satirical parody message presented by the Wavy Baby shoes in the Vans case was not readily perceived from the product "without the accompanying manifesto or descriptions" that were used in marketing and packaging the shoes. In contrast, the play on the "well-known 'my other car ...' " joke in My Other Bag served to further distance the MOB bags from Louis Vuitton bags. See 602 F. Supp. 3d 358 (E.D.N.Y. 2022), aff'd, 88 F.4th 125 (2d Cir. 2023) (discussed above).

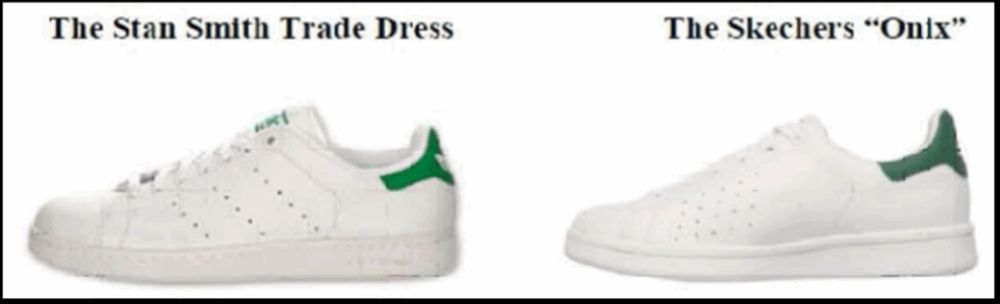

adidas America, Inc. v. Skechers USA,

Inc. (2018)

Likelihood of Confusion as to Shoe Design

adidas, a global athletic footwear designer and retailer, sued competitor Skechers, alleging that Skechers' "Onix" shoe infringed on and diluted the unregistered trade dress of adidas' "Stan Smith" shoe. adidas Am., Inc. v. Skechers USA, Inc., 890 F.3d 747 (9th Cir. 2018).

Since its release in the 1970s, the Stan Smith shoe, named after tennis player Stan Smith, has been one of adidas' most successful products. The Court noted that it had extensive media coverage and received numerous accolades including being named Footwear News' 2014 "Shoe of the Year." Id. at 752.

adidas further alleged that the trade dress of Skecher's "Relaxed Fit Cross Court TR" shoe infringed and diluted adidas' "Three-Stripe" trademark.

The Court noted that adidas' Three-Stripe mark, for which it owns federal trademark registrations, was a staple of adidas' brand, and that adidas claimed it had earned hundreds of millions of dollars in annual domestic sales of products that bear the Three-Stripe mark.

The District Court granted adidas' preliminary injunction motion barring Skechers from manufacturing, distributing, advertising, and selling both the Onix and Cross Court shoes. Skechers appealed to the Ninth Circuit which upheld the injunction as to the Onix shoe, but reversed as to the Cross Court shoe.

The Ninth Circuit found that the adidas had established that the Stan Smith shoe was distinctive, emphasizing the extensive evidence of secondary meaning (acquired distinctiveness) such as celebrity placements and marketing by adidas. The Ninth Circuit also noted that Skechers' use of metadata tags like "adidas Stan Smith" on its website supported an inference of intentional copying, likening it to "posting a sign with another's trademark in front of one's store." Id. at 755. In assessing similarity of trade dress, the Ninth Circuit found that the shoes' visual similarities like white leather uppers, green heel tabs, and perforated stripes, created an overall impression of similarity. Minor differences, such as the Skechers logo, did not overcome the similarities.

But the Ninth Circuit reached a different conclusion for the Cross Court shoe, holding that adidas failed to demonstrate irreparable harm. While the Ninth Circuit agreed that the Three-Stripe mark was both conceptually and commercially strong, it found that adidas' theories on harm it suffered were too speculative. adidas argued that Skechers' lower-priced Cross Court shoe would dilute its brand image, but the Ninth Circuit found no concrete evidence that supported the conclusion that consumers viewed Skechers as an inferior brand or that post-sale confusion would damage adidas' reputation.

This holding underscores how courts scrutinize claims of secondary meaning (acquired distinctiveness), brand dilution, and irreparable harm in fashion IP cases.

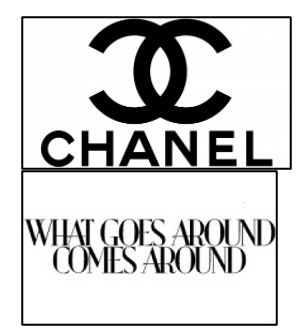

Chanel, Inc. v. What Goes Around Comes

Around (WGACA)

(2025)

Trademark Infringement In The Resale Market

In a closely watched case involving the re-sale market for apparel, Chanel sued What Goes Around Comes Around (WGACA), a luxury vintage goods retailer, for trademark infringement including selling counterfeit Chanel products and allegedly misrepresenting their relationship with Chanel. Chanel, Inc. v. What Goes Around Comes Around, LLC, et al., Case No. 1:18-cv-02253, 2022 WL 902931 (SDNY March 28, 2022). Chanel alleged that WGACA, through its advertising using the Chanel trademarks, was trying to "deceive consumers into falsely believing [that it] has some kind of ... affiliation with Chanel or that Chanel has authenticated the [pre-owned] goods [it was offering up] in order to trade off Chanel's brand and goodwill."

WGACA argued that it should not be liable because Chanel's lawsuit was an impermissible attempt at barring the legitimate resale of used products on the secondary market. Further, WGACA claimed that it used Chanel's trademarks to simply identify the products, not to claim any affiliation or sponsorship by Chanel.

After nearly six years of litigation, a unanimous jury held in favor of Chanel and awarded $4 million in statutory damages in February 2024, and the court soon issued an injunction prohibiting the use of Chanel's trademarks and imagery. In June 2025, the District Court denied WGACA's motion for a new trial, upholding the $4 million jury verdict.

The decision has been heralded as a key victory by fashion and apparel companies. This case challenged how luxury resale businesses market their products, encouraging a more cautious approach when referencing third parties in their advertising. That said, WGACA has filed a Notice of Appeal to the Second Circuit. As of September 2025, briefing has not yet occurred in the appeal.

Chanel, Inc. v. TheRealReal,

Inc. (ongoing)

Responsibilities of Resale Platforms

In a similar case to Chanel v. What Goes Around Comes Around, Chanel sued TheRealReal, a San Francisco-based luxury goods resale platform, for trademark infringement, selling counterfeit Chanel products, misrepresenting its authentication process, and other claims in 2018 in the US District Court, Southern District of New York (Case No. 1:18-cv-10626-VSB). Among other things, Chanel contended that The RealReal's assurance of authenticity for its Chanel resale items misled consumers and damaged Chanel's brand reputation. Chanel further asserted that The RealReal falsely misrepresented the relationship between the two companies, creating the illusion of an affiliation where there was none.

The RealReal contended that its rigorous authentication process ensured the genuineness of the products sold and that any counterfeit items were anomalies. The RealReal also argued that it clearly and transparently identified itself as a reseller and did not imply an affiliation with Chanel, and that the use of the Chanel name constituted nominative fair use. In a 2020 ruling, the District Court dismissed Chanel's claims for trademark infringement and false endorsement/unfair competition under the Lanham Act, but denied a motion to dismiss Chanel's claims for counterfeiting, false advertising, and unfair competition under New York common law. The RealReal amended its Answer to raise antitrust counterclaims.

The case was stayed for about two years in order for the parties to pursue settlement, but no settlement was reached. Recently, in October 2025, after a pre-trial conference, the Court issued an order setting new deadlines.

Hermès International v. Mason

Rothschild (MetaBirkins)

(2023)

Trademark Rights in Digital Assets

Hermès International v. Rothschild arose from a dispute over the boundaries of trademark protection in the digital art and NFT space. 678 F. Supp. 3d 475 (S.D.N.Y. 2023). Hermès, the luxury fashion house known for its "Birkin" handbag, sued artist Mason Rothschild, whose "MetaBirkin" NFTs depicted furry, digital versions of the iconic bag. Hermès alleged that Rothschild's NFTs infringed and diluted its Birkin trademarks under the Lanham Act and falsely implied Hermès' sponsorship or approval of the project. Rothschild countered that his NFTs were protected by the First Amendment as artistic expression.

Following a nine-day trial, a jury in the Southern District of New York found Rothschild liable for trademark infringement, dilution, and cybersquatting related to his "MetaBirkins" NFTs, awarding $133,000 in damages. The jury concluded that Rothschild, a self-described "marketing strategist," intentionally sought to mislead consumers into believing his NFTs and the associated "metabirkins.com" website were affiliated with Hermès. Id. at 481. The Court, applying the Rogers v. Grimaldi, 875 F.2d 994 (2d Cir. 1989) test, had instructed jurors that Rothschild's work enjoyed First Amendment protection unless Hermès proved that Rothscdhild had intentionally misled consumers, and the jury found that Hermès met that burden. Post-trial, Rothschild moved for judgment as a matter of law or, alternatively, a new trial, while Hermès requested a permanent injunction.

The court held that its jury instructions were, if anything, more favorable to Rothschild than required, because they defined "explicitly misleading" as "intentionally misleading," placing a higher burden on Hermès. Id. at 485. The court noted that any intentional attempt to deceive consumers fell outside the First Amendment's protections and likened Rothschild's conduct to commercial fraud rather than artistic commentary. Accordingly, the Court denied Rothschild's motions for judgment as a matter of law and for a new trial.

As for the injunction, the court granted it in favor of Hermès after finding undisputed evidence that Rothschild continued promoting and profiting from MetaBirkins NFTs post-verdict. Applying the four-factor test from eBay v. MercExchange, the court held Hermès sufficiently demonstrated irreparable harm that the confusion would impede Hermès ability to control its reputation and launch its own NFT initiatives. The Court found that legal remedies were inadequate because Rothschild's ongoing use signaled continued infringement. Balancing hardships, the court rejected Rothschild's claimed First Amendment injury, reasoning that he had waived his First Amendment protection when he intentionally "exploit[ed] the goodwill and reputation of Hermès." Id. at 491.

Rothschild appealed to the Second Circuit on July 24, 2023 (Case No. 23-1081). Oral argument was held on October 23, 2024, and the case remains pending as of October 2025. While NFT's may not be as popular as when the case started, the appeal presents interesting questions. The Second Circuit's eventual ruling is expected to clarify how the First Amendment interacts with trademark rights in the context of NFTs and other digital goods, and to define whether traditional trademark principles should apply to virtual representations of branded products.

Vidal v. Elster

(2024)

Free Speech and the Name Clause of Lanham Act

In Vidal v. Elster, a 2024 U.S. Supreme Court case, the Court examined the Lanham Act's "Names Clause." 15 U.S.C. § 1052(c); Vidal v. Elster, 602 U.S. 286 (2024). Applicant Steve Elster had sought to register the trademark TRUMP TOO SMALL for t-shirts and hats with the United States Patent & Trademark Office (USPTO). See Serial No. 87749230. The USPTO denied the application, citing the Lanham Act's Names Clause, which prohibits registration of trademarks that falsely suggest a connection with a living person. After appeals to the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board and Federal Circuit, the Supreme Court ultimately heard the case.

Elster argued that the USPTO's denial violated the First Amendment because TRUMP TOO SMALL was intended as a criticism of President Donald Trump. The USPTO countered that the Lanham Act, among other things, had the purpose of protecting the privacy of individuals and that restricting registration of individuals' names without their consent is necessary to prevent commercial exploitation of personal names. Further, doing so avoids misleading the public about the source and endorsement of goods.

The Supreme Court agreed with the USPTO, holding that the Names Clause passed First Amendment muster. The Names Clause imposes a content-based but viewpoint neutral restriction on speech. The Court analyzed whether such a restriction was permissible under the First Amendment as a matter of first impression, noting that while content-based regulations of speech are "presumptively unconstitutional," they are inherent in the application of trademarks. The Court concluded that due to the rich history of restricting the unauthorized use of a person's name, the Names Clause is constitutionally valid. For more on this case, see this Article by Fennemore's Mario Vasta.

Notably, a few months after the adverse Supreme Court decision, Elster filed a new application to register TRUMPTOOSMALL.COM for "online retail clothing stores services rendered in virtual environments") on September 18, 2024. See USPTO Serial No. 98755909 and https://trumptoosmall.com. The USPTO issued an Office Action again refusing registration under the Names Clause. The application is still pending.

Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros. Inc.

(2000)

"Secondary Meaning" for Trade Dress

Consisting of Product Design

Going back in time a bit further, and going "up to eleven" in this list, the Supreme Court's decision in Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros. Inc., 529 U.S 205 (2000) is a landmark case under Lanham Act jurisprudence. In Wal-Mart, the Supreme Court unanimously held that a plaintiff asserting a claim of infringement of unregistered trade dress based on a product's design must prove that the design has acquired secondary meaning (i.e., that consumers recognized the product design as signifying the maker of the product). In other words, product design is never inherently distinctive as trade dress, but only protectable upon a showing of secondary meaning.

Samara Bros, Inc. made a line of children's clothing. Wal-Mart Stores contracted with a supplier to make children's outfits based on the Samara clothing line which were sold under Wal-Mart's house label "Small Steps." Samara was not happy with these alleged "knockoffs" and brought an action for infringement of unregistered trade dress under Section 43(a) of the Trademark Act of 1946. 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a). Although the jury found for Samara, Wal-Mart filed a motion for judgment as a matter of law, claiming that there was insufficient evidence to support the conclusion that Samara's designs were protected as distinctive trade dress. The District Court denied the motion and the Court of Appeals affirmed the denial of the motion.

But the Supreme Court reversed and found in favor of Wal-Mart, stating that in a "Section 43(a) action for infringement of unregistered trade dress, a product's design is distinctive, and therefore protectible, only upon a showing of secondary meaning." The Court analogized product design to color, which it had earlier found was also not inherently distinctive in Qualitex Co. v. Jacobsen Products Co., 514 US 159 (1995). And the Court also noted that because "product design almost invariably serves purposes other than source identification that this fact "not only renders inherent distinctiveness problematic; it also renders application of an inherent-distinctiveness principle more harmful to other consumer interests."

In contrast, trade dress consisting of product packaging can still be found to be inherently distinctive, and protectible, without a showing of secondary meaning.

It is interesting to note that the Supreme Court also suggested that clothing designers could "ordinarily obtain protection for a design that is inherently source identifying (if any such exists), but that does not yet have secondary meaning, by securing a design patent or a copyright for the design—as, indeed, respondent did for certain elements of the designs in this case. The availability of these other protections greatly reduces any harm to the producer that might ensue from our conclusion that a product design cannot be protected under § 43(a) without a showing of secondary meaning." Id. at 214 (emphasis in italics added).

But as the Court clarified seventeen years later in Star Athletica (discussed above), copyright protection for apparel designs is generally limited to those elements of the design that could be considered separate from the overall apparel design. For a variety of legal and practical reasons, design patents continue to be an underutilized form of protection in the industry.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.