An April 2025 report from the Initiative for Medicines, Access & Knowledge (I-MAK) titled,"The Heavy Price of GLP-1 Drugs,"presents grossly misleading information regarding the patent protection for semaglutide products (marketed by Novo Nordisk under the trademarks Ozempic, Rybelsus, and Wegovy) and tirzepatide products (marketed by Eli Lilly under the trademarks Mounjaro and Zepbound). The report accuses Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly of engaging in patent abuse to extend protection for their products. This accusation is predicated on I-MAK's assertion that these companies own large numbers of patents covering their respective products. But, as the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) noted in its recentDrug Patent and Exclusivity Study, "simply quantifying raw numbers of patents and exclusivities is an imprecise way to measure the intellectual property landscape of a drug product because not every patent or exclusivity has the same scope."

Moreover, I-MAK's assessment of the numbers of patents relevant to those products is itself misleading, because the analysis uses unreasonably broad search terms without limitation to the part of the patent that spells out the rights of the patent holder (i.e., the claims). Indeed, for many of its search terms, I-MAK searched across the entire text of the patent, including the specification, without further analysis of whether theclaimsof the patent were relevant to the products at issue, leading to the identification of patents that do not claim the products at issue and would not be barriers to generic competition.

In the months following the publication of their report on "The Heavy Price of GLP-1 Drugs," instead of correcting their overly broad search strategy to reflect the actual number of patents protecting these products, I-MAK doubled down on misleading statements about the role of patents on drug prices in a subsequent report published in June, titled"Overpatented, Overpriced: A Data Brief on Medicare-Negotiated Drugs: Eliquis, Ozempic, Rybelsus and Wegovy."In this report, I-MAK recycled its misleading statements about semaglutide products, allegations of delays of competition due to statutorily granted patent term, and so-called "patent thickets."

The supposed "data" and methodological approach that I-MAK relies upon for identifying patents associated with the pharmaceutical products in its reports to allege large numbers of patents and prolonged periods of patent protection for these products has long been subject to scrutiny. In fact, Senator Thom Tillis (R-NC) in January of 2022 wrote to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the USPTO seeking an independent assessment of both the I-MAK data and data contained in a database called the Evergreen Drug Patent Search (also called the Hastings Evergreen Database or Evergreen Drug Patent Database). Senator Tillis separately wrote to I-MAK seeking disclosure of their (at the time) non-public patent search strategy for drug products disclosed in prior reports. In response to this directive from Senator Tillis to the FDA and the USPTO, a jointDrug Patent Studywas published by the USPTO on June 7, 2024, that called into question every conclusion about numbers of patents and years of patent protection in prior I-MAK reports. Moreover, analysis of USPTO's Drug Patent Study has led to conclusions—including by theCouncil for Innovation Promotion (C41IP),Professor Adam Mossoff (writing for the Hudson Institute),Deborah Collier (writing for Citizens Against Government Waste), andPatrick Kilbride (writing for IP Watchdog)—that the data generated and discussed in the I-MAK reports is suspect, if not downright inaccurate.

Here, we address the overly broad and misleading search strategy I-MAK employed in its April 2025 report to identify inflated numbers of patents alleged to be barriers to generic competition for semaglutide and tirzepatide, respectively. Additionally, we address two patent "trends" identified in I-MAK's June report related to "patent term extensions" and "follow on patenting and patent thickets." These latest reports only further call into question the validity of I-MAK's assertions, which are widely cited and relied on by policymakers, the media and others.

Flawed Search Strategy

I-MAK's use of overly inclusive search strategies, including broad search terms, resulted in I-MAK identifying an inflated number of patents and published patent applications (referred to as "patent applications" in this article) it asserts are "related to" semaglutide and tirzepatide products, respectively. Notably, I-MAK included patentapplicationsin its searches, though a patent application does not confer any exclusionary rights to the patent applicant until and unless a patent is granted on the patent application. I-MAK did not report any strategies to investigate whether the results from its searches actually claim the products at issue or present a barrier to generic entry. For example, while I-MAK reportedly employed its broad search terms across patent text other than just the claims (and for some terms, across the entire text of the patent), I-MAK failed to investigate what was actually claimed in the resulting patents. I-MAK also neglected to investigate whether the patents it identified were in force when the respective products were approved. As a result, and as noted below, many of the patents identified by I-MAK are not "related to" the approved products and would not be barriers to generic entry.

A. Semaglutide

As noted above, I-MAK's use of overly inclusive search strategies resulted in I-MAK identifying patents that would not be a barrier to entry for a generic of Novo Nordisk's semaglutide products. For example, I-MAK included in its search terms a naturally occurring partial sequence of GLP-1, resulting in patent applications disclosing GLP-1 itself as well as its precursors. I-MAK also searched for patents and patent applications merely referencing GLP-1 anywhere in the title, abstract, and claims. I-MAK reported an inflated number of patents and patent applications as purportedly "related to" semaglutide without considering what subject matter was actuallyclaimed.

The inclusion of unfocused search terms allowed I-MAK's report to mistakenly assert that the earliest patent applications "related to" semaglutide were filed in 1993, amounting to an alleged period of 49 years of patent term in total (with over 40% of the so-called 49 years of protection occurring before semaglutide was even approved by the FDA). The issued patent I-MAK appears to be referencing is U.S. ReissuePatent No. 37302, titled "Peptide." This patent does not claim semaglutide and, along with several other of the patents I-MAK identified as so called "related to" semaglutide," expired prior to the regulatory approval of the initial semaglutide product (Ozempic). As such, none of those patents could have presented a barrier to generic entry.

B. Tirzepatide

The April report likewise employed overly broad and nonspecific search terms that resulted in the inclusion of expired patents that would not be a barrier to entry for a generic of Eli Lilly's tirzepatide products, which are all currently under regulatory exclusivity granted by the FDA. I-MAK searched for patents and patent applications referencing GLP-1 or GIP, as well as a hormone other than GLP-1 or GIP, anywhere in the title, abstract, and claims. I-MAK also searched within the titles, abstracts, and claims of patents and patent applications for non-specific terms that would capture analogs for an entire group of insulin-controlling hormones, not just tirzepatide. Again, I-MAK reported an inflated number of patents and patent applications as purportedly "related to" tirzepatide with no analysis of whether those patents and applications actuallyclaimtirzepatide.

These broad search terms resulted in I-MAK inaccurately asserting that the earliest patent applications "related to" tirzepatide were filed in 1997, resulting in an alleged total period of 44 years of patent protection (with over half of the so-called 44 years of protection occurring before tirzepatide was approved by the FDA). The issued patent I-MAK appears to be referencing, U.S. Patent No.6,006,753, is titled "Use of GLP-1 or Analogs to Abolish Catabolic Changes After Surgery." This patent does not claim tirzepatide and, along with abouta thirdof the issued patents that I-MAK alleges are "related to" tirzepatide, expired before a tirzepatide product even gained regulatory approval and could not be a barrier to generic entry.

Statutory Patent Term Extensions

The I-MAK reports suggest that statutory provisions providing for patent term beyond the 20-year term measured from the filing date of a patent application constitute a "trend" of delays to entry of generic medicines. For example, in footnote 3, the June report states: "[t]he pharmaceutical industry lobbied for Patent Term Extensions under the Hatch-Waxman Act 1984 to ensure they would be guaranteed up to 14 years of market protection from the date of a product's approval. Patent Term Extensions are a policy designed to compensate the patent holder for loss of patent term as a result of any regulatory delays."

What the footnote fails to mention, and the report as a whole overlooks, is that the Hatch-Waxman Act balances benefits, rights and responsibilities of both innovators and generics in the pharmaceutical industry. The statutory scheme was designed to enable entry of generic drugs, while also supporting innovation. While the provisions related to patent term extension (PTE) reflect a benefit to the innovator pharmaceutical industry, the footnote fails to mention the multiple benefits provided to the generic drug industry by this statutory scheme, including the ability to pursue abbreviated new drug applications that rely on the innovator's findings of safety and effectiveness of a product. The related amendments to the Patent Act also included the safe harbor provisions that allow for uses of patented inventions, prior to patent expiration, that are reasonably related to the development and submission of information for regulatory approval. Prior to these provisions, generic drug development required costly and time-consuming clinical programs and could not begin prior to innovator patent expiration without possible threat of patent enforcement. In sum, both innovative pharmaceutical companies and generic drug companies benefitted from the amendments to the Patent Act promulgated under the Hatch-Waxman Act. And the Hatch-Waxman Act has beenextraordinarily successfulin promotinggeneric competition: today, 90% of all U.S. prescriptions are filled with generics, up from 19% in 1984, before the passage of the Act.

The June I-MAK report (as well as the April report) also points to statutory provisions that afford term to patents in the form of Patent Term Adjustment (PTA), which was codified under the American Inventor Protection Act of 1999 (AIPA). The report does not capture the need Congress recognized when passing the AIPA, which included the PTA provisions. That need was brought about by the change in patent term from 17 yearsfrom grantto 20 yearsfrom filing, leaving the term of a resulting patent subject to forces outside the control of the patentee, including delays by the USPTO. In order to rectify shorter patent term due to delays in processing and examination at the USPTO, Congress enacted PTA. Notably, the change to patent term and the PTA provisions apply to all utility patents, not just patents related to pharmaceuticals.

While not stated in I-MAK's reports, the PTE provisions nonetheless limit the total amount of enforceable patent term granted by extension imposing a 14-year cap measured from the drug approval date. That is, the amount of patent term remaining on the date of approval plus the term to be granted as PTE cannot exceed a total of 14 years, including any PTA. Further, while PTA can be granted to any patent due to USPTO delays, PTE can only be awarded to one patent for an approved product. And the exclusionary rights during the extended period are limited to the approved product as set by statute.

So-Called Follow-on Patenting and Patent Thickets

I-MAK also alleges in its June report (and similarly addresses in its April report) that pharmaceutical companies seek numerous follow-on patents covering "minor modifications" of the original patented invention to create so-called "patent thickets." I-MAK does not explain what it considers a "minor" modification" but, without justification, seems to suggest that it includes any innovation coming after the initial "key compound patent" for a product. That sweeping and unsupported dismissal of later patent filings ignores significant innovative advancements to products, such as formulations that offer improvements that benefit patients, including through greater stability (and thus, longer shelf life), new and approved administration routes, reduced side effects, and fewer doses (and thus, potential for greater patient compliance). It also ignores innovation that leads to new therapeutic options for previously untreated diseases, new combination therapies, and many other possible advancements that benefit patients. Patent protection provides the incentive to continue pursuing such innovation without limiting competitors' ability to practice earlier innovations when the patents protecting those innovations expire.

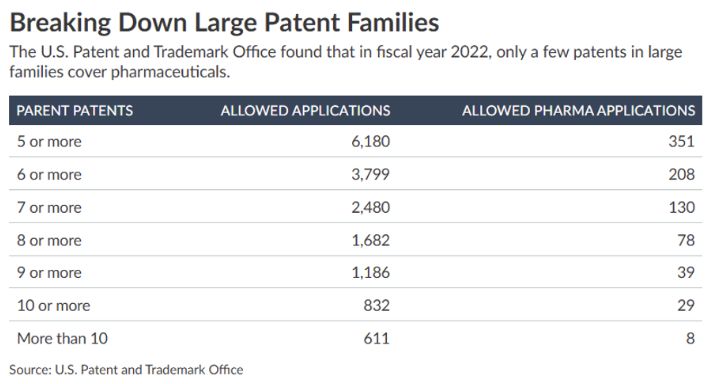

Earlier in June, theUSPTO presentedon the results of a five-year study on applications with "large" patent families, defined as patent families having five or more parent patent applications.

As part of that analysis, USPTO provided the following breakdown of patent families with a focus on those in the pharma examination space:

As shown in the above table, the percentage of patent applications having multiple parent applications to which benefit is sought are more frequently coming from areas of technology outside of pharma. These findings underscore the role ofmisleading rhetoricregarding patent thickets in the pharmaceutical sector.

Bad Facts Make Bad Policy

Policy making needs to be driven by facts and context, not narratives derived from false, misleading and inaccurate data. Analyses based on such data fail to ensure that policy decisions on patent protection and innovation are founded in accurate data to identify changes to be made for the better of the system for all patentees and patent applicants.

Originally published by IP Watchdog

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.